Challenges

Red tape

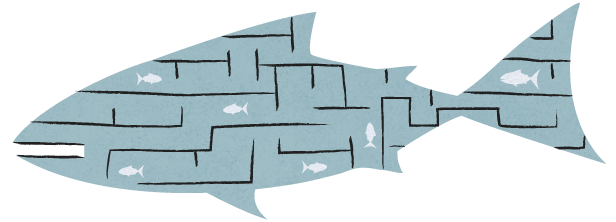

Multiple agencies—including county, state, and federal—across multiple departments (Commerce, Defense, Agriculture) all have jurisdiction over different aspects of U.S. fisheries. Enforcement of laws and ensuring compliance by fishers and distributors/processors requires navigating an obstacle course of red tape that is costly for all involved. This complexity is amplified in the case of highly migratory species that each year swim across international and regional boundaries, passing through perhaps six or seven distinct fisheries, all with rights to catch the fish during that journey.

Politics vs. Science

Scientific advisory panels set catch limits using mathematical models based on data from independent surveys and catch landing records. But fisheries regulations are set by political bodies, which historically have compromised the science at the expense of the fish stocks—Atlantic Cod and Atlantic bluefin tuna are two examples.

Science vs. Experience

From the fishers’ perspective, regulation and stock assessments can seem capricious and incongruent with what they see on the water, which leads to mistrust and acrimony. For example, in the U.S., stock surveys are repeated once every three years in the same geographic locations, even though fish aren’t bound to those areas. The mathematical models assume uniformity, constant lifecycle, and consistent environmental processes and conditions. Fishers say that can lead to lower catch limits when fish have merely moved to different habitats in the region. Conversely, because assessments are done only every three years, the “corrective” impact on fishers is dire if quota was set too high: Despite three years of legal fishing within limits under a managed plan, in 2013 the cod fishery in New England was declared a “disaster” and catch limits were reduced by 80 percent. That has led to financial ruin for many small-boat fishers.

Our enormous seas

Tracking boats on the water and what they’re catching has historically been an impossible task. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) or “pirate” fishing remains rampant, especially in international waters. An estimated $23.5 billion worth of illegal fish are caught each year.

Barely there inspection

The FDA inspects less than 1% of imported seafood, which accounts for 90% of U.S. seafood consumption. Limited resources for enforcement and inspection are typical of fisheries around the globe and drive IUU and other unsustainable practices.

Opportunities

Better data, better decisions

New technology—such as improved vessel monitoring systems, apps to report catch data, and bar-coding for fish—improves accuracy of catch statistics, allowing for more effective, adaptive management models and detection of IUU. These solutions also allow fish to be valued as a premium product with a traceable, verifiable history, rather than as a commodity.

Community-managed

New fisheries-management models, such as catch shares, can give “ownership” of fish in the water to individual fishers. Other models limit access to certain fishing regions, based on agreements to leave other areas untouched as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), enforced by locals. These models, if supported with the right business structures and supply chains, can encourage long-term stewardship ethics and citizen participation, and can result in higher returns for fishers.